Part 3: Building ships in Calcutta

James Bonner’s story continued. Uncovering how a Scottish man from humble beginnings was linked to the colonisation of South Australia

James Bonner (my 4x great grandfather) journeyed to Bengal in the early 1790s with the East India Company and started his own blacksmithing business in Calcutta in 1805. This next part of the story delves into the expansion of his enterprise, building ships on the Hooghly river. We uncover how a Scottish man from humble beginnings built the ship that played a key role in the colonisation of South Australia.

The first mention I’ve found of James Bonner and his ship enterprise, is in April 1807. There is an advertisement in the Calcutta Gazette where James is selling a ‘newly constructed’ ship called the Vulcan. We can assume James actually built this ship, because a few years later, in 1812, we see the below advertisement, where it is being resold after the subsequent owner dies. James must have garnered enough of a positive reputation to be named in the advertisement and for the ship to be referred to as ‘…one of the best sailing boats on the river’.

The advert mentions that the boat is ‘coppered to the bends’. Strangely, this phrase nowadays means that something is completely worn out and unusable, which doesn’t gel with the fact the boat is apparently ‘…one of the safest boats on the river…’! We can assume that in this case, it means the boat’s hull has been sheathed with copper. This was a technique that the English Royal Navy experimented with starting in the 1760s, to increase the lifespan of their ships, protecting them from attack by shipworm, barnacles and other marine growth. James would have been familiar with this technique from his time at the dockyard in Woolwich and was well placed to do this with his blacksmithing knowledge.

Aside from building and selling ships, James diversified his income streams by owning a few ‘fast sailing and safe passage boats’ which were used to transport gentlemen to Saugor, Balasore and Cuttack. These are key locations down the river Hooghly, out into the Bay of Bengal, so it’s likely gentlemen travelled to these places for business. Saugor Island is where the River Ganges meets the sea, so it’s also a place of pilgrimage, although I don’t expect the boats were used for this purpose.

By 1813, we see that James owns a ship yard with James Horsburgh. This is the same man who took over from Alexander Robertson, a cooper on Clive Street (See Part 2). With Horsburgh’s experience crafting with wood (a cooper typically built casks and barrels) and Bonner’s skills in blacksmithing, this turned out to be a successful partnership. The collaboration between Bonner and Horsburgh led to the building of the two key merchantman ships in James Bonner’s story: the Severn (1812) and the Hindostan (1813).

I don’t have much more information yet on Bonner and Horsburgh’s shipyard, other than the fact it was on the Hooghly river, likely at Sulkea (on the opposite side of the river from Calcutta). James lived in Sulkea in his early years in India, and there were many dockyards there. The below picture is about 50 years after the time they built the Severn and the Hindostan, but it gives an idea of what the area might have been like.

The Severn and the Hindostan are important in James Bonner’s history because these were the ships that transported James and his (large) family back to London. Despite building a successful life in India and surviving countless tropical diseases, crocodiles, gharials (a creepier looking crocodile!) and the fury of the bengal tiger, James did in fact return home. Well, almost! He made it to the most northerly town in England, settling in Tweedmouth, Berwick Upon Tweed. I’ll cover more on this (and his many women!) in another post.

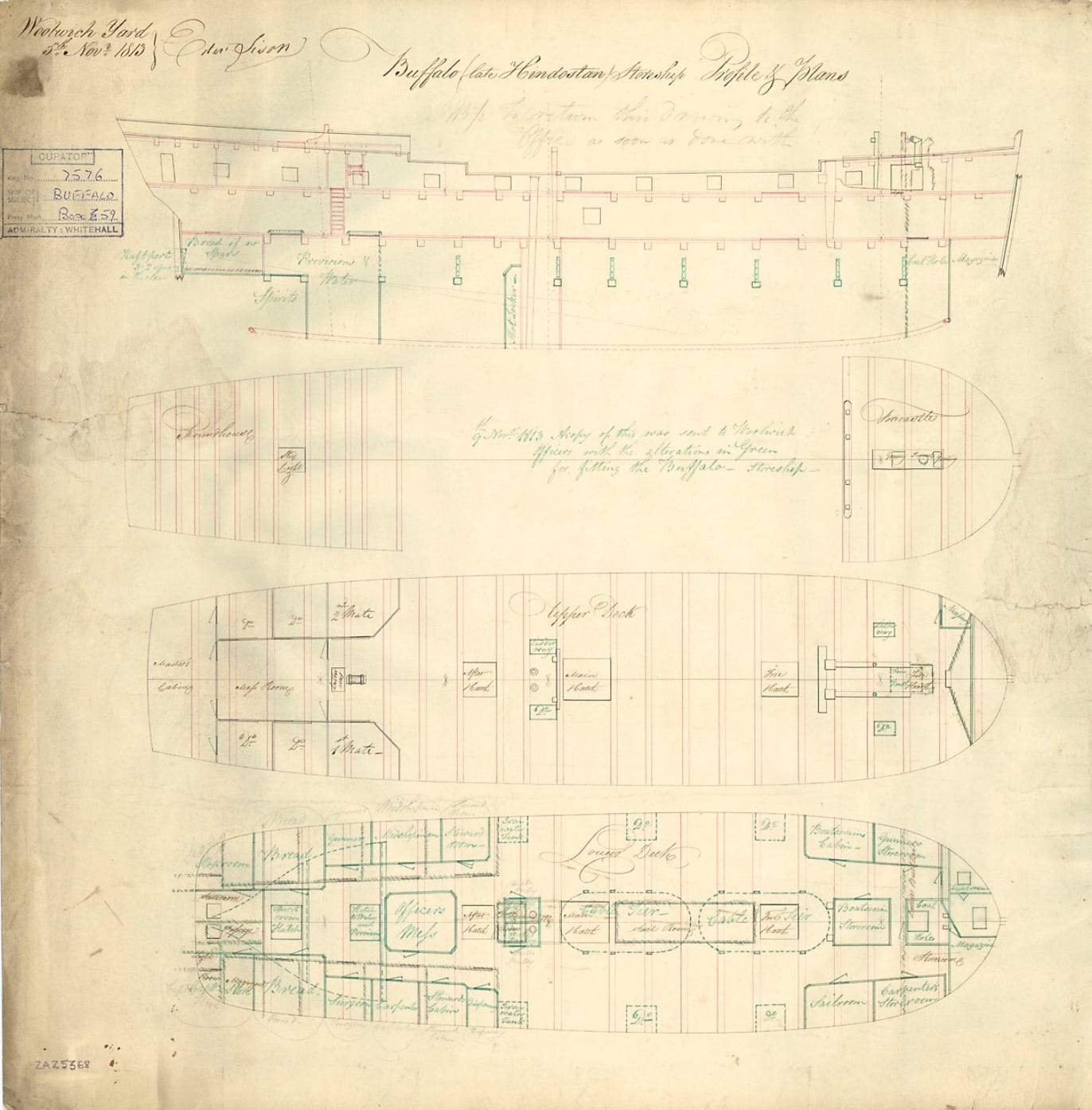

Horsburgh, being a fellow Scotsman, joined Bonner on the trip back to London, where they then sold the two ships to the Royal Navy. I always thought there was something quite poetic about building your own transport home! The Severn was renamed by the Royal Navy to ‘HMS Camel’ and the Hindostan was named ‘HMS Buffalo’. I haven’t yet discovered why they chose these names, but it could be because both these animals are well known for their ability to carry heavy loads, the ships being intended for transporting goods around the world.

While both HMS Camel and HMS Buffalo had decent lifespans for merchantmen, it’s the latter that has the more interesting life. HMS Buffalo was originally fitted out as a store ship and used in the Napoleonic Wars. The below plan from the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich shows the adaptations (in green) made to the original layout which Bonner and Horsburgh designed.

HMS Buffalo was converted for different uses over its lifetime. As well as being a quarantine ship (to quarantine goods to prevent the spread of Cholera), it was also kitted out as a convict ship to transport female convicts to New South Wales, Australia (1833). I’m planning to highlight a few of the histories of the convict women aboard HMS Buffalo soon, some of whom were banished to the other side of the world with incredibly young children, to start a new life under the shadow of their former ‘corruption’.

HMS Buffalo was also later used as an emigrant ship to transport settlers to Australia (1835-6). This is when we see it being used to deliver the first governor of South Australia, Captain John Hindmarsh to establish the colony in 1836. Due to this, South Australians (and some New Zealanders, since HMS Buffalo eventually ended up as a shipwreck there) now have a soft spot in their hearts for HMS Buffalo, creating songs, museums, life size replicas and postage stamps all commemorating the historic vessel.

HMS Buffalo deserves its own detailed post, so I’ll put one together at some point. In the meantime, here are some further reading resources so that you don’t need to rely on my erratic writing schedule 😆.

Thanks to Dorothy Ramser (another James Bonner ancestor) for providing additional clues 😉 you can read some of her articles on James Bonner and his ships here: