HMS Buffalo’s only Murderess: Georgian Convict, Janet Stewart

I’m writing a series of posts uncovering the lives of the 179 female convicts who were transported from Britain to Australia in 1833 on board the ship my 4x Great Grandfather built, HMS Buffalo. Read more here.

This next post is about the woman branded as HMS Buffalo’s most dangerous passenger - the only criminal on board convicted of murder. This is the story of Janet Stewart.

The majority of female convicts who were transported to Australia on board HMS Buffalo in 1833 were convicted of petty theft. Seven years’ transportation for stealing a length of cotton. Fourteen for pocketing a handkerchief if it wasn’t your first offence. This was true for the majority of women transported to Australia in the 19th century, harshly punished for small crimes because the government needed more women in the colonies…

However, like today, a fully fledged murderess was a rare spectacle, and HMS Buffalo had one of its very own. Janet Stewart was convicted of murdering her brother-in-law in 1832 and sentenced to transportation for life.

Interestingly, (or rather, shockingly) although her crime was the most heinous of the 179 female convicts aboard HMS Buffalo, earning her labels in the papers such as ‘wretched creature’, and part of a ‘depraved and incorrigible’ group of people - seventeen of the other women were also sentenced to life. Their crimes included robbing their masters or mistresses, stealing money and committing highway robbery. Poor Jean White stole a hat and despite it being her first offence, was sentenced to life. It must have been some hat… I wonder how these women felt when they understood their sentences to be equal to Janet’s punishment for alleged murder.

I say alleged because there still remains some doubt about Janet’s guilt in the crime. So here is her story so that you can decide for yourself…

In the spring of 1832, Janet was around 29 years old and married to a man called Duncan Stewart. They had three children together, the youngest being around five years of age. They traveled throughout Scotland, well known in the highlands as part of a familial group that at the time were referred to as ‘Gypsies’ or ‘Tinkers’. ‘Tinkers’ was commonly used to describe Scottish travellers1, because they were originally a group of people known for mending tin pots and pans.

Janet and her family slept in tents constructed with large sticks that they carried on their backs, cooked outdoors on fires and earned money via various odd jobs including selling spoons which they whittled themselves from animal horn. They travelled with Duncan’s brother David and his wife, Mary McPhee and their child.

On the 17th of May, 1832, Janet, Duncan and the rest of their party were travelling through Perthshire. When they tried to enter the town of Dunkeld, they were turned away by police. Presumably this was because, like today, nomadic people in Britain are often mistrusted and land ownership laws don’t accommodate their culture of camping anywhere. Regardless, the party continued on South, stopping at a wooded area in Little Dunkeld. These very same woods are those which feature in Macbeth, when the three witches prophesied that Macbeth shall never be vanquished, until Great Birnam wood moves to high Dunsinane hill. Which it did, when the Scottish soldiers camouflaged themselves with branches from the wood to attack Macbeth’s castle at Dunsinane.

Janet and her party also made good use of the branches from Birnam Woods, using some to build a fire for the night, while Duncan and David selected a few choice staffs for themselves. Duncan waved his stick around, demonstrating to some local men and boys who had come to gawk at them the differences between how the English and Irish fight. He said he could take on three Irishmen at once, no, seven! By this point of the night, Duncan, David and the whole party were roaring drunk, having consumed at least 5 gills (1.5 pints) of whisky which they had exchanged for some horn spoons at the nearby Birnam Inn. Wanting to continue the fun, David later sold one of the dogs for another flagon of whisky.

William McIntosh, a maltster from the nearby Birnam Distillery, along with James Robertson and John Christie, both young workers at the Birnam Inn were walking along the road that ran past Janet’s encampment at twilight. The Stewarts had drawn quite a crowd it seems, reportedly because of the raucous noise that was coming from around their fire as they drunkenly argued with each other. McIntosh reports that Janet and her children were sitting on the pavement at the side of the road, one younger child strapped to her back. McIntosh gave one of the boys a halfpenny and Janet said “God bless you” to him, then asked if she could have another to buy some tobacco. McIntosh then offered Janet some unsolicited advice, along the lines of ‘stop quarrelling and go eastward to a more comfortable place and keep the children warm’. However, in the meantime, Janet’s husband Duncan, not content with demonstrating his stick-fighting prowess, was now threatening McIntosh and party with said stick, so they ran away from Duncan, towards the inn. I suppose entertainment was lacking around Birnam Inn that night, as the group returned later to continue their ogling, under the cover of a nearby tree. It was lucky they did, as they were all called up as witnesses to what unfolded soon after.

Between 9 and 10pm that night, Janet and her party were all gathered around the fire and loudly arguing again. The witnesses said that Janet and Duncan walked away from the group, carrying a parcel of sticks on their backs used to construct their tents. Presumably they were about to settle down for the night. However, it’s reported that Duncan’s brother David called after them, challenging Duncan to a fight, threatening he would ‘by his soul… do for him with the stick’. Duncan threw off his coat and accepted the challenge, bringing forth his own stick. Janet reportedly shouted “wait a wee” or perhaps “wait till you see” (witnesses weren’t sure), while one of Janet’s children yelled “Oh, he’ll kill ye, father”. David snapped his stick in two across his knee to make a better fighting instrument and the two bothers went head to head, a dog jumping up at them as they fought - some witnesses said it looked like David was winning. Now this is where things get a little foggy in the reports…

McIntosh, the brewer, says that Robertson, one of the boys from Birnam Inn, shouted something in Gaelic to David’s wife who was still over towards the fire. Perhaps trying to call her over to intervene. McIntosh was momentarily distracted from the fight by this and as he turned his head back, he was met face to face with David, who was looking wildly into his eyes, spluttering “She has a knife”. David then staggered back and fell down, never to rise again. David had been stabbed four times in the chest and once in the back of the neck, blood blossoming through his shirt. His wife Mary ran over to David’s body but he was already dead. Janet lay crying on the road. Duncan still clung to his stick, hitting it off the ground.

None of the witnesses could definitively say who stabbed David. The night was dark, with no moonlight. They all had difficulty placing Janet during the fight, each offering slightly differing or conflicting memories of where she was positioned at each stage. Christie, the boy from Birnam Inn said he saw Janet strike David twice on the breast at one point, but didn’t see anything in her hand at the time.

Regardless, the police were called for and they apprehended Janet and Duncan at a shed not too far away. Christie and another servant from the Birnam Inn were there when the Stewarts were apprehended and reported that Janet asked to be let outside to get a drink, but while doing so crouched by a hedge. Both witnesses then heard a noise that sounded like broken glass and as Janet returned, she allegedly asked the officers to search her pockets. They instead went to search the hedge and found a knife - although one account says they just found the handle.

Janet and Duncan were both taken to Perth Gaol and tried for murder. However, it was clear that no one really knew which of them committed the crime. The wording of the trial reflected this uncertainty, using phrases like “ …murdered by the said Duncan Stewart, and Janet Stewart, or one or the other of them.” Janet gave two declarations, five days apart. In her first, she says that she had been attending to her child and was nowhere near the fight, not hearing of it until she was awoken in the shed by the police and accused of the murder. She suggested it must have either been Davids wife, Mary who stabbed him, or his brother, Duncan as no one else was there. She denied throwing a knife over the hedge. In her second declaration, Janet altered her story to say that she had missed the brothers fighting because she went to light her pipe by the fire after someone had given her child a halfpenny. Then, as she was sitting by the side of the road, her husband Duncan called to her and said to come away as “I have stuck my brother very sore”. She then implored him to run but he would not. When showed the knife supposedly used in the murder, she said it looked like one that Duncan and David used for carving spoons.

After the evidence was given at the trial, the Advocate Deputy stepped up to address the jury. He stated that the evidence suggests it was the female, Janet, who committed the murder. Taking this and running with it, Duncan’s counsel, Mr Murray, then told the jury that if the Advocate Deputy thinks this, then the only logical verdict for Duncan would be ‘Not Guilty’. Mr Horseman, the counsel for Janet, now had his work cut out for him. Despite Janet never admitting she committed the murder, Mr Horseman rested her defence on the idea that she did it only to defend her husband, who it had been proved was in imminent danger. He said it wasn’t premeditated, but spur of the moment defensive attack once she saw that her children feared for their father’s life. He then tried to convince the jury to label the act as ‘culpable homicide’ so Janet could avoid the death sentence and instead be transported. The lesser of two evils. Quiet fell as Lord Gillies prepared to give the final word. He assured the jury that they could not reasonably or conscientiously arrive at any other verdict than ‘Guilty of the crime of murder’ for Janet.

With little option left open to them, the jury deliberated for 15 minutes and returned with their verdict. Acquittal for Duncan. Unanimous vote of ‘Guilty’ for Janet. However, the jury had been swayed by the patchy evidence and Mr Horseman’s pleas and therefore ‘strongly, earnestly and unanimously’ begged for the mercy of the crown, hoping to spare Janet from the noose.

Lord Gillies assured Janet he would send the jury’s request to the right department, but not to get her hopes up. He then reached for his black cap, placing it on his head as he read out her sentence - death by hanging, on the 31st of October 1832, with her body to be buried within the precinct of the jail. The jury were in uproar, they pleaded with his Lordship to intervene with the crown on Janet’s behalf, for the sake of her infant and aged mother.

As the 31st of October approached, the Perth locals grew excited for a spectacle they hadn’t seen in some time - two hangings on one day (Yippee!). A murderess, Janet Stewart, convicted of killing her brother-in-law and a murderer, John Chisholm, accused of murdering his wife! However, as the crowds poured in on the morning of the execution, discontentment grew as they learned that the hanging of the murderess, Janet, was to be postponed, a special messenger having arrived from the Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne just two days previously. The merciful jury’s pleas had reached the right ears. But that wasn’t all. It turned out that there was some new information that had come light about the crime which required further investigation. As Janet had been dragged away to the jail after her sentencing, one of her children had made a scene, saying that it was their father, Duncan who had murdered David, not Janet. The police were on the lookout for Duncan for further questioning.

The postponement of her execution had come just in time for Janet who was reportedly in a bad way - “…the poor wretch’s horror of her approaching doom had preyed so much upon her frame that, from the state of extreme debility and exhaustion to which she was reduced, she must have been actually borne to the scene of her exit from this world”. Although she was cautioned against getting her hopes up, the respite helped to revive her a little. She still vehemently denied the murder, blaming Duncan.

Her execution continued to be delayed, a three week reprieve here, a month there, until the middle of December 1832, when it was finally decided that her sentence would be changed to transportation for life. She would live. But what would this new life be like? After a further few months in jail, she finally received word that she would be sent to embark HMS Buffalo on the 19th of April 1833, beginning her journey to Australia. The rest of her travelling community heard this news and young and old gathered in Perth to see her off, reportedly getting roaring drunk. Two women, one believed to be David’s widow, Mary, went to visit Janet in jail. Janet asked to see Duncan and the women obliged, bringing him along. It’s not known what they discussed, but afterwards, Duncan and the women stopped off in town on the way home to lose themselves in whisky. Mary’s new husband had to come looking for them and carried Mary home on his back with another bottle of whisky in hand.

On the 29th of April 1833, just ten days after Janet’s departure to London, the body of David’s widow, Mary, was found naked in a ditch, covered in severe wounds. She was heavily pregnant. The police immediately rounded up and arrested the party that had attended Janet’s leaving gathering, including her husband, Duncan - who was the prime suspect. The papers were now convinced that Duncan was the real murderer of his brother. The Perthshire Courier reported that “Janet’s transportation has again been arrested, and she brought back to our jail.” But the problem is, I can’t find any evidence that they did bring Janet back. On the 26th of April, HMS Buffalo’s surgeon, noted that he received three prisoners from Perth. Janet had already arrived in London before the body was found. He makes no further note that any were disembarked. The police investigation into Mary’s death was fruitless, with everyone released, including Duncan without charge due to lack of evidence. Janet sailed for Australia on the 4th of May 1833, her five year old boy in tow.

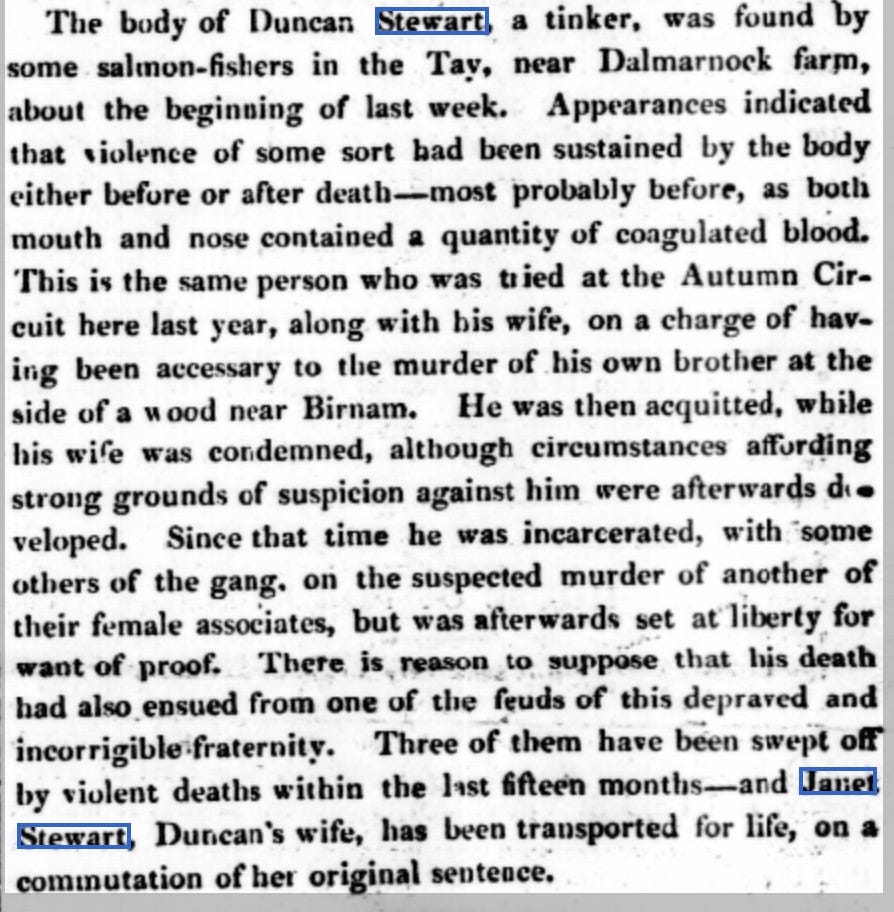

In August of 1833, while Janet was still at sea, somewhere past Rio in the South Atlantic Ocean, Duncan’s body was found washed up by Salmon fishers in the Tay, near Dalmarnock. He had met a violent death, his mouth and nose filled with coagulated blood.

Unknowingly now widowed, Janet sailed into Sydney harbour on the 5th of October 1833 and was selected to be a servant for a Mr Charles Wright in Sydney. She must have behaved well and worked hard as she was presented with a ticket of leave in 1842, just ten years after her arrival in New South Wales, which allowed her to live in Illawarra. She even received a conditional pardon just five years later, in 1847. This was much better than a ticket of leave as she wasn’t confined to live in just one area of the colony, but could travel anywhere she liked (as long as it wasn’t the United Kingdom or Ireland, of course). She even re-married. Just three years after her arrival in Australia she met Thomas Childerly, another ex-convict who had been transported from Cambridgeshire in 1818 for sheep stealing. They married in 1836, in Dapto, Wollongong when Janet was 32 and Thomas was 44, having lived most of his adult life in Australia. Some sources suggest they went on to have children - all of whom would have been classed as free citizens.

We’ll never know for sure if Janet was wrongly accused of murder, but it’s nice to think that perhaps her new life in Australia was a better ending for her - away from the tribulations of her drunken and violent husband. Perhaps the skills obtained from her nomadic life came in extremely useful in the conditions required to survive and thrive in a new colony.